LGBTQ+ stories

A look at diverse stories of love and desire in the Royal Collection.

Reading time: 5 minutes

LGBTQ+ stories can be found across the Royal Collection. Diverse forms of love and identity have always existed, but LGBTQ+ experiences have often been left out of history or rewritten. This article highlights some of the stories of that diversity and celebrates LGBTQ+ identities across different periods and cultures.

The terms we use today to talk about LGBTQ+ identities did not exist in the past – many of the individuals would not have identified as LGBTQ+. Where possible, the language employed by the artist or sitters to define themselves has been used alongside their writing. Their words give voice to a long history of diverse desires.

Sappho

The poet Sappho lived around 630–570 BC in Mytilene on the Greek island of Lesbos. Her poems are powerful expressions of love and longing for both men and women. In one, she describes how seeing the woman she loves and hearing her laughter:

makes my panicked heart go fluttering in my chest, for the moment I catch sight of you there’s no speech left in me

The marble statue of Sappho was created by William Theed in 1851. At the time this statue was created, her passionate declarations of same-sex desire were downplayed. Translators changed the subjects of Sappho’s poems from female to male, or altered the tone to make Sappho’s love seem more like friendship. Despite attempts to rewrite and redefine Sappho, her descriptions of female intimacy and love have endured. The terms ‘Sapphic’ (from her name) and ‘lesbian’ (from Lesbos, the place she lived) are now used to describe female same-sex desire.

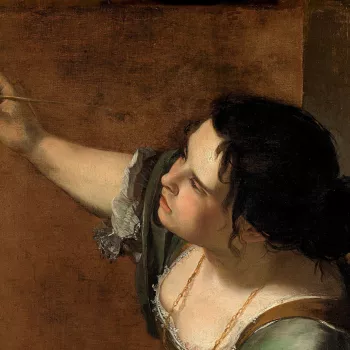

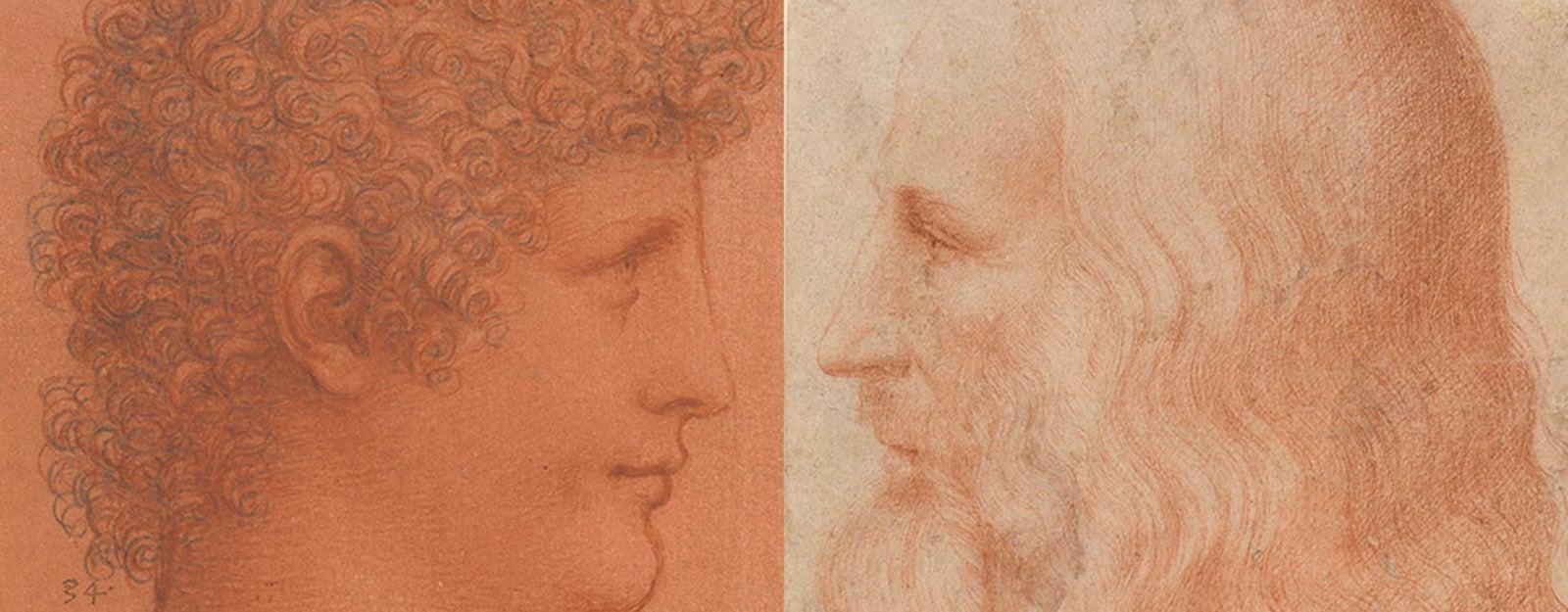

Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo, the renowned artist and inventor of the Renaissance era, had male companions during his life. Same-sex relationships between men were common in Renaissance Florence. However, in 1432, pressured by a growing moral panic, the Florentine government established the ‘Office of the Night’ to prosecute men accused of being involved in same-sex relationships. In 1476, Leonardo was brought in front of the Office of the Night but the charge was dropped.

There is little other evidence of Leonardo’s sexuality, though we know he never married and lived instead with male companions, most notably his pupils Gian Giacomo Caprotti and Francesco Melzi.

Gian Giacomo Caprotti – nicknamed Salai by Leonardo – is described as a ‘beautiful youth with fine curly hair, in which Leonardo greatly delighted’. Drawings of curly-haired youths appear in Leonardo’s notebooks; although these drawings are not portraits of Salai, they show the impact his features had on Leonardo’s ideal of male beauty.

Francesco Melzi was Leonardo’s primary assistant for the last decade of the artist’s life and was a talented artist in his own right. Melzi cared for Leonardo through his final illness and inherited Leonardo’s notebooks and papers, some of which can be found in the Royal Collection today.

Michelangelo

When Michelangelo was 57 he met and fell in love with the young Roman nobleman Tommaso de’ Cavalieri. Michelangelo was devoted to Cavalieri and wrote him sonnets that ardently express his love:

Love takes me captive; beauty binds my soul / Pity and mercy with their gentle eyes / Wake in my heart a hope that cannot cheat

Alongside poems and letters, Michelangelo made a series of complex and highly finished drawings for Cavalieri, including this one. Executed in black chalk, the drawing shows the Fall of Phaeton.

Apollo, the sun god, offered to grant his son Phaethon one wish and Phaethon asked to drive the chariot of the sun. Phaeton lost control of the horses, and to save the earth from being scorched, Jupiter struck him from the heavens with a bolt of lightning. The story is one of pride and failed ambition, and the drawing has often been thought to represent Michelangelo’s feelings of unworthiness in presuming to love the beautiful Cavalieri.

Chevalier D'Éon

The Chevalier D’Éon was a decorated soldier, spy, and diplomat who spent the first half of their life living as a man before permanently presenting as a woman. While living as a woman in London, D’Éon earned money through fencing demonstrations. D'Éon's famous fencing match, depicted in a painting, showcases their prowess and challenges gender norms. D’Éon’s opponent was the Chevalier de Saint-George – an expert fencer and favourite of George IV when he was Prince of Wales.

Though it is tempting to view D’Éon as transgender in a 21st-century sense, it is important to recognise this terminology did not exist during their lifetime. However, we do know that in their autobiography, D’Éon identifies as female and explains they were encouraged to live as a man by their family, to secure an inheritance.

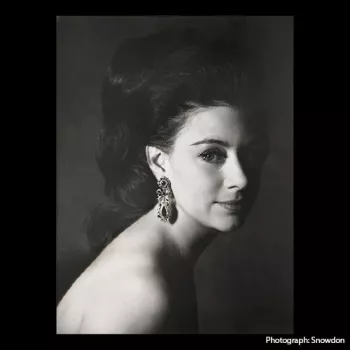

Rosa Bonheur

Born in Bordeaux in 1822, Rosa Bonheur was the leading animal painter of her day and arguably the most famous female painter of the 19th century. Bonheur keenly observed her subjects from life, visiting slaughterhouses and horse markets. These were male-dominated spaces, and Bonheur obtained a permit from the French authorities to dress in menswear to avoid harassment. Throughout her life, Bonheur cut her hair short and wore masculine clothing which provided her with a greater level of freedom.

As far as males go, I only like the bulls I paint.

Rosa Bonheur had two long-term relationships with women. She met her first partner, Nathalie Micas when they were both young and the two lived together for over 40 years. Following Nathalie’s death, Bonheur met and fell and love with the American artist Anna Klumpke. Bonheur described her relationship with Anna as ‘a divine marriage of two souls’. Bonheur’s openness about her relationships was remarkable at a time when female same-sex desire was widely condemned.

Oscar Wilde

Now celebrated as one of the most famous poets and writers of the 19th century, Oscar Wilde was persecuted and imprisoned for his sexuality. Wilde had relationships with men throughout his life, most famously with Robert Ross and Lord Alfred Douglas. In a letter to Douglas, the otherwise eloquent Wilde wrote:

I have no words for how I love you.

In 2017, Wilde received a posthumous pardon under the Alan Turing Law. The law pardoned thousands of men who had been historically convicted under anti-gay laws between 1885 and 2003. Wilde’s life and work have proved hugely influential in the LGBTQ+ community and beyond.

A volume of Wilde’s first published work, simply titled Poems, was presented by the poet to Albert Edward, Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII) in 1881.

David Hockney

David Hockney is one of the best-known LGBTQ+ artists alive today. When Hockney began his career, male homosexuality was still criminalised in Britain. In 1964, he moved to the more liberal California. Hockney views his depictions of gay relationships as ‘good propaganda,’ and his work has consistently celebrated and represented gay life, often focusing on domestic, intimate moments.

Throughout the latter part of his career, Hockney experimented with new technologies to produce graphic art. His self-portrait created on an iPad shows Hockney calmly meeting the viewer’s gaze.