Holbein in the Royal Collection

A closer look at Hans Holbein's works.

Holbein’s portrait drawings

How did Hans Holbein create these wonderful drawings?

By Rachael Smith, Senior Paper Conservator and Victoria Button, Head of Paper Conservation

Reading time: 7 minutes

The Royal Collection includes 80 portrait drawings by Hans Holbein. Although beautiful works of art in their own right, Holbein’s portrait drawings had another purpose, as preparatory studies for potential oil paintings or miniatures.

Paintings and miniatures could be slowly built up over many hours, but the drawings were created more rapidly, in front of the sitter. This immediacy resulted in their greater animation but influenced Holbein's choice of materials. As there is little archival evidence for Holbein’s work, this article looks closely at the drawings themselves to reveal his working practice.

The drawing materials used by Holbein were familiar to 16th-century European portrait artists and readily available everywhere he worked. It is therefore not what materials he used but how he used them that is of interest. The variation in detail created by using materials in different ways demonstrate that he was not dependent on a single, rigid technique. Instead, each drawing appears a spontaneous response to the individual being drawn, and each rewards careful viewing with unique discoveries.

Holbein’s drawing papers

Holbein chose good quality handmade paper as a readily available and flexible surface for his portrait drawings. When held up against the light, many of his sheets reveal watermarks: symbols within the paper that indicate the mill where they were made.

There are a wide range of different watermarks found on his drawings, some of which indicate that he was using papers imported from across Europe: mainly from France, with a few that are Swiss or German in origin.

The drawings have been trimmed so their original size is unknown, but examining the positioning and orientation of the watermarks shows that Holbein drew some on whole sheets but many on half, or quarter sheets. Occasionally he extended the paper by adhering on an additional strip.

Creating a skin tone

Holbein sometimes drew his portraits directly onto the white paper, but this required a relatively lengthy application of drawing material to create the skin tone. Modelling, the suggestion of a three-dimensional shape, was built up largely through shadow.

More often, he prepared the papers by painting one side with a pink coating and allowing it to dry in advance. This enabled more efficient use of his time with the sitter to capture their unique features with less media. The mid-tone also allowed modelling through white highlights as well as shadows, a technique closer to that of the painting which might be created from the drawing.

A range of pink shades can be seen across the different drawings, probably to reflect the variation in the sitters’ skin tones. Analysis has revealed common components of white chalk, red vermilion, yellow ochre and lamp black pigments, probably bound together with an animal glue mixed with warm water. Experimentation with recreating this preparation has revealed the wide range of pinks that can be achieved by varying the proportions of just these four colours.

Holbein's use of chalk

The powdery quality and limited colours of the drawn lines indicate that Holbein captured his sitter’s initial likeness with chalks. Black, white, red, brown and yellow chalks all occur naturally in the earth. Once quarried, they were cut into sticks, sharpened, and could be placed in a cylindrical holder for drawing.

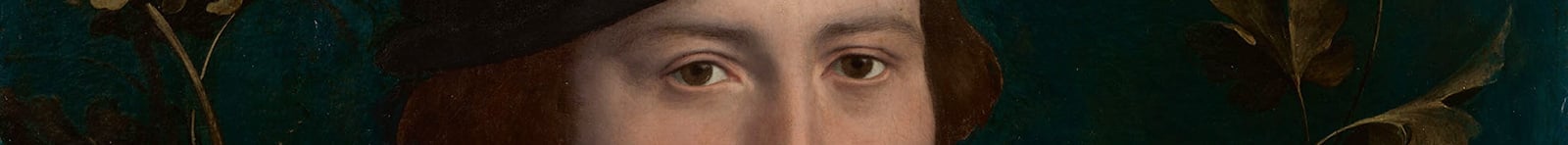

Chalks enabled rapid sketching and, unlike paint, didn’t require drying time so that Holbein could continuously work up his drawing in front of the sitter. He initially drew his figures in black chalk, except for delicate areas, such as the eyes and lips, which he drew in red chalk.

Chalk responds to pressure so tentative lines could be lightly sketched in and then reworked or confirmed with a heavier, darker line. The chalk sticks were sharpened to a point for detailed work or allowed to soften for broader parallel hatching strokes to build shadow. Advantage could also be taken of the natural variations in tone, cohesiveness and hardness of chalks from different deposits.

Chalk lines can be readily smudged by a finger or with a stumping tool made from coiled paper, leather or cloth. Holbein created great subtly of modelling within the faces by initial hatching with red, black and brown chalks, and then softening and blending them in this way.

He used a wider range of coloured chalk and textural effects to capture clothing, jewellery, and hair. Alongside stumping, he occasionally wet out drawn lines with a brush and water to spread and even out the chalk. He layered these different effects to create depth, texture, and pattern, for example by stumping a base of one colour and then laying sharp strokes of different colours on top.

Holbein's use of watercolour

Despite the versatility of chalks, their colour and tonal range are limited, and Holbein enhanced many of his portrait drawings with final touches of watercolour paint.

Watercolour pigments were available from a much wider variety of sources than natural earths, including man-made materials as well as minerals, insects and plants. This resulted in a fuller range of colours and Holbein used watercolour to depict blue or green eyes, hues not available in natural chalks.

The pigments were bound with gum arabic, a natural tree gum, and diluted with varying amounts of water to create paints of different strengths. While luminous eyes were created with transparent washes, Holbein made full use of stronger, saturated black and white paints to increase the tonal contrast of highlights, shadows and contours.

Lead white, made by deliberately corroding lead metal, was stronger and brighter than white chalk. It can be seen in a small number of the drawings, especially of women, in flesh highlights, the whites of eyes, and in clothing.

Holbein used a rich, saturated carbon black watercolour, made from soot, to deepen shadows, block out dark areas of clothing and to reinforce his outlines, the element of the drawing most likely to be directly transferred to a painting support. More nuanced shading within faces was created by diluting the black down to grey or using a brown watercolour.

Across the drawings. there is great variation in the amount of watercolour applied. A small number are heavily worked up, perhaps due to more time available with the sitter, or a greater expectation that a painting commission would follow.

The initial chalk outlines and face modelling of these two drawings (below) have been applied in a similar way as for the other portrait drawings, but the eyes, hair and clothing have subsequently been much more heavily worked up with watercolour.

Clothing and jewellery

Subtly drawn faces are often in contrast to the more roughly sketched clothing of the sitters. However, costume and jewellery were important indicators of the sitters’ identity and status and would therefore require careful depiction in a finished painting.

Close inspection reveals that Holbein captured the important details with impressive efficiency. He sometimes indicated the colour and fabric through written annotations, rather than drawing, and indicated small sections of repeating pattern that were sufficient to allow later reconstruction of the whole. In contrast, unique details of jewellery were carefully depicted, sometimes in enlarged details to the side of the sitter.