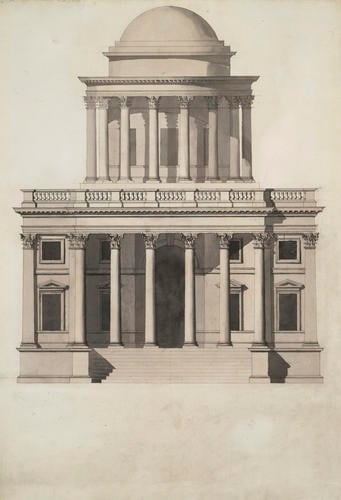

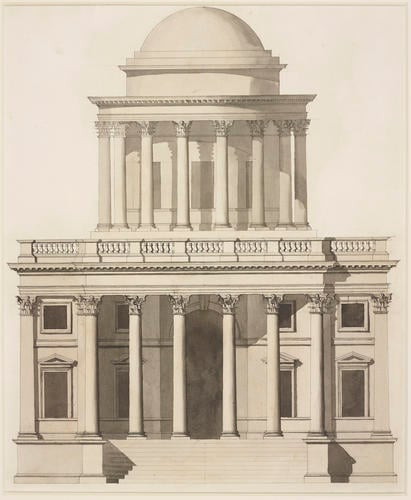

A design for a domed Corinthian building c. 1760

Pen and ink over pencil and wash | 56.4 x 38.8 cm (sheet of paper) | RCIN 980435

-

A wash drawing showing an elevation of a Corinthian building. The rectangular building is shown with a projecting portico, with steps that lead up to the centre. A circular temple is shown on top of the building.

Among the King’s designs are a number in which two or more elements are combined to form a more or less unified whole. In the case of the present design, a circular temple is placed on top of a square or rectangular building with a projecting portico. George III’s interest in domed structures was clearly encouraged by Chambers, who made a number of designs with this combination, most notably in his designs for St Marylebone Church in the 1770s. Unlike those designs, most of the King’s architectural projects were made as exercises, without the intention that they would ever be built.

The King’s drawings vary from the polished (as here) to the crude. The extent to which he was assisted in the drawing-up of his architectural designs will probably never be known. However, in March 1765 ‘the person who works about the king in all the designs in architecture which the king invents or directs himself’ was identified - in a letter from the 6th Earl of Findlater to Mr Grant - as Mr Robinson. This useful individual was William Robinson (c.1720-75), a member of the Office of Works from the 1740s and Clerk of Works at St James’s 1754-66; he appears to have been acquainted with Thomas Worsley. Robinson served unofficially as Chambers’s clerk of works at Buckingham House from the start of the King’s building activities there and was formally appointed to this position in 1769; he was appointed Secretary to the Board of Works in 1766.

In spite of their close professional relationship, Chambers was frequently critical of Robinson, who was evidently more skilled as a draughtsman and administrator than he was as an architect. He supervised the alterations at Carlton House for the Dowager Princess of Wales in the 1760s, ‘agreeable to HM’s Instructions’ and apparently to Robinson’s designs, but without adequate budgetary regulation and much to the displeasure of Chamber. In June 1774, after seeing Robinson’s designs for Somerset House, where Robinson was Clerk of Works from 1762, Chambers commented to Worsley that it was ‘strange that such an undertaking should be trusted to a Clerk in our Office, ill-qualified as appears . . . while the King has six architects in his service ready and able to obey his commands. Methinks it should be otherwise in the reign of a vertuoso prince’.

Robinson’s sudden death in October 1775 left the way open for Chambers himself to take over the Somerset House project. While any designs produced by the King after 1775 were clearly not the work of Robinson, we can only guess at how many of his designs before that date were actually drawn by the King. In the same way, it is clear that Chambers would have had time to draw up only a fraction of the designs commissioned from him by the King.

Catalogue entry adapted from George III & Queen Charlotte: Patronage, Collecting and Court Taste, London, 2004 -

Medium and techniques

Pen and ink over pencil and wash

Measurements

56.4 x 38.8 cm (sheet of paper)

Object type(s)