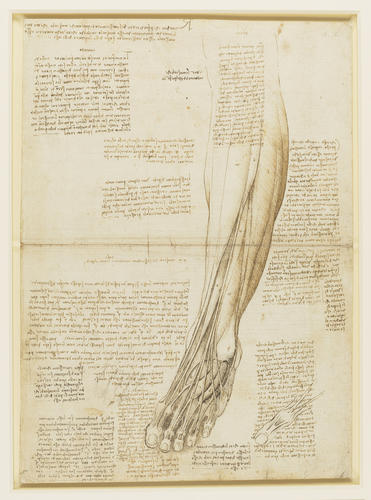

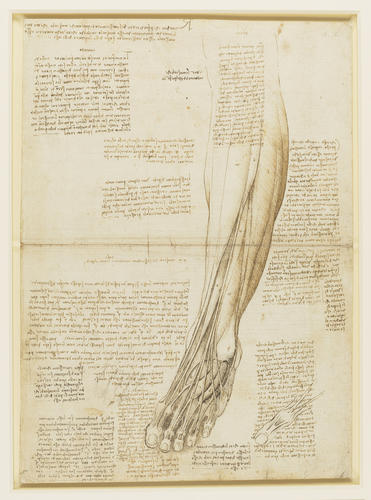

The muscles and tendons of the lower leg and foot c.1510-11

Black chalk, pen and ink, wash | 38.9 x 28.2 cm (sheet of paper) | RCIN 919017

Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519)

919017 R.jpg c.1510-11

Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519)

919017 V.jpg c.1510-11

-

A double folio from Leonardo's 'Anatomical Manuscript A': A study of the anatomy of the left foot and leg from just above the knee, showing muscles and tendons; a small study of the big toe; notes on the physiology of contraction of the muscles and erection of the penis.

Many of the structures shown here are the same as those seen in RCIN 919016. The interactions of the tendons of extensor digitorum (and hallucis) longus and brevis are again well displayed – the inset diagram at lower right depicts the arrangement of the three middle toes, not the big toe as its size might suggest – though the brevis muscles appear in the drawing to have their origins on the lateral malleolus rather than on the calcaneus. Several muscles of the lower leg are shown, including tibialis anterior, fibularis longus, and fibularis tertius (not found in all individuals, and here correctly placed in the anterior crural compartment). Neither here nor in any other image of the human leg did Leonardo depict the tendinous structures known as retinacula, the dense fibrous bands that extend around the ankle to keep the tendons in place during flexion and extension (cf. his earlier dissections of the bear’s leg, 919372-5).

In the notes, running to some 1,200 words, Leonardo revisits themes treated throughout the Anatomical Manuscript A, with reminders or exhortations to draw the bones separately, from all sides, and then joined; then adding the muscles, drawing them as threads to convey their multilayered structure, and so on. He also considers the physiology of muscle ‘enlargement’ (contraction) and erection of the penis. Ancient Greek physiology held that muscles contracted by being inflated with ‘pneuma’, systemic air that circulated within the body and was involved in the functioning of the organs. Leonardo doubted that this ‘air’ could possibly inflate a muscle so quickly and deflate so quickly, and that the volume of air that would need to be compressed to harden a large muscle would be more than could be moved through the nerve fibres:

"What is it that enlarges a muscle so quickly? They say it is air. And where does it retreat to when the muscle diminishes with such speed? Into the nerves of feeling which are hollow. Then there would have to be a great wind to enlarge and elongate the penis and make it as dense as wood, such that air was reduced to such a density. Indeed there would not be enough in the nerves, and even if the whole body were full of air there would not be sufficient. And if you say that it is the air in the nerves, what air would it be that courses through the muscles and reduces to such hardness and power at the time of the carnal act? For once I saw a mule that could barely move from the fatigue of a long journey under a great load, and seeing a mare, immediately its penis and all its muscles swelled up, in such a way that its forces were multiplied and it reached such a speed that it caught up with the fleeing mare, which was forced to submit to the desires of the mule."

Text from M. Clayton and R. Philo, Leonardo da Vinci: Anatomist, London 2012Provenance

Bequeathed to Francesco Melzi; from whose heirs purchased by Pompeo Leoni, c.1582-90; Thomas Howard, 14th Earl of Arundel, by 1630; probably acquired by Charles II; Royal Collection by 1690

-

Creator(s)

Acquirer(s)

-

Medium and techniques

Black chalk, pen and ink, wash

Measurements

38.9 x 28.2 cm (sheet of paper)

Other number(s)