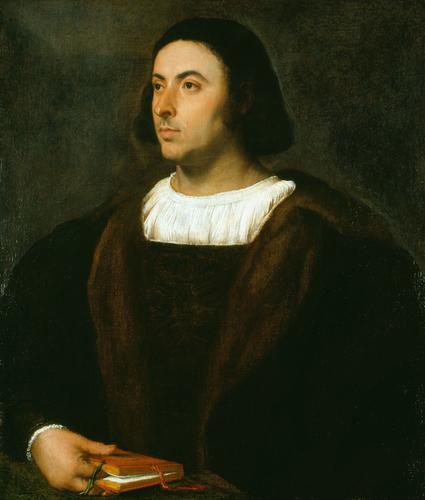

Portrait of Jacopo Sannazaro (1458-1530) c. 1514-18

Oil on canvas | 85.7 x 72.7 cm (support, canvas/panel/stretcher external) | RCIN 407190

-

Titian’s portraiture was much admired; early in his career, he recorded the features of friends, writers and Venetian noblemen before his international fame led to commissions from Emperor Charles V, the Pope and King Philip II of Spain. This imposing portrait shows a nobleman gazing fixedly forward, lost in thought, his finger tucked into a book to keep his place. It has been suggested that he is the Neapolitan poet and humanist Jacopo Sannazaro (1458-1530).

Now generally accepted as by Titian, the work has been recently restored to reveal the subtle play of the brown-patterned damask of the saione or skirted jerkin against the dark brown fur lining and the black of the gown. The background would originally have been a subtle, paler grey, giving a cool depth, so that the man’s black silhouette stood out against it more clearly, as shown in the print by Cornelius van Dalen the Younger for the Reynst collection.

The portrait has been dated variously from c.1511 to the early 1520s. The style of the subject’s square-necked saione and gown (both with large, bulbous upper sleeves), the wide-necked chemise, the length of his hair with centre parting and the fashion for an indication of a moustache must date the work before 1520 and probably closer to 1513. The sitter wears the sober colours that were typically worn by Venetian male citizens over the age of 25. This portrait seems to fit into Titian’s career between the Portrait of a Man with a Quilted Sleeve of c. 1510 (National Gallery, London) and his Man with a Glove of c.1523 (Louvre). The half-length view and the fact that Titian experimented with a parapet places this work closer to the National Gallery painting. This earlier date is confirmed by the dress, which resembles other works dated to before 1520. The Louvre portrait exhibits slightly later fashions: shorter hair and the collar of the chemise tied at the neck. Titian seems to have favoured a restricted colour range in these early portraits, with cool blue-grey or green-grey backgrounds.

The fact that the sitter has his finger in a book links him with portraits of humanists and writers. Various literary candidates have been suggested over the years: a seventeenth-century print after this portrait, by Cornelius van Dalen the Younger, is labelled as Giovanni Boccaccio; in the nineteenth century the portrait was variously identified as Alessandro de’ Medici, Duke of Florence and Pietro Aretino. The name Jacopo Sannazaro was first proposed in 1895. The suggestion accords with an early copy of the painting (Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool) inscribed 'Sincerus Sannzarius': ‘Actius Sincerus’ was a pseudonym much used by Sannazaro.

Jacopo Sannazaro was a humanist and poet from a noble Neapolitan family. Except for a brief exile in France in 1501-4 he lived and worked in Naples, serving as court poet to King Ferdinand I and belonging to Giovanni Pontano’s humanist academy. His principal work, Arcadia (1502-4), is an Italian-language version of the classical pastoral, encompassing love, poetry and nostalgia, which was very influential throughout the sixteenth century, whether on the landscapes of Giorgione and Titian or the poetry of Spencer, Sidney and Shakespeare. It is not surprising that Venetians might have wanted to paint or to own a portrait of this famous Neapolitan: Sannazaro’s work was published in Venice; he corresponded with the Venetian humanist Pietro Bembo, and composed an epigram dedicated to the city.

One problem with this identification is that the this portrait would seem to depict a thirty-year-old and yet, as we have seen, the clothes, cut of hair and style of painting date it to c.1512-15, when Sannazaro was in his mid-fifties. This is not impossible: In his portrait of Isabella d’Este (Royal Collection), Titian rendered the 60-year-old as a 30-year-old. As in that case, Titian could here have based the poet’s features on an earlier portrait (of c.1490), while depicting him in clothes that would have been fashionable in c.1513. The question therefore remains of whether this face records Sannazaro’s appearance in c.1490. His likeness is known to us through a variety of images, including three medals, from which many later printed versions derived. These images of Sannazaro (most of them recording the appearance of a much older man) seem to match the Royal Collection portrait in the thick eyebrows, set of the eyes, long, slightly beaky nose and the heavy jaw. But there are features which do not appear in the present work. Titian might also have been expected to inscribe a portrait of such a famous man as he did with his 1523 portrait of Baldassare Castiglione (National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin). In the end, the idea that this portrait depicts the inventor of the Renaissance pastoral is an attractive one, but is hard to prove. Titian’s unsurpassed skill at characterisation conveys an imposing, erudite and intelligent man; whether it is Sannazaro or another humanist has yet to be decided.

Catalogue entry adapted from The Art of Italy in the Royal Collection: Renaissance and Baroque, London, 2007Provenance

Gerard Reynst, Amsterdam; acquired by the States of Holland and West Friesland and presented to Charles II in 1660

-

Creator(s)

Acquirer(s)

-

Medium and techniques

Oil on canvas

Measurements

85.7 x 72.7 cm (support, canvas/panel/stretcher external)

103.1 x 88.0 x 7.3 cm (frame, external)

Category

Object type(s)

Other number(s)

Alternative title(s)

Anonymous man with a book in his hand, previously identified as

Alessandro di Giuliano de' Medici ( ), Duke of Tuscany, previously identified as

Boccaccio, Giovanni ( ), previously identified as

Aretino, Pietro ( ), possibly previously identified as