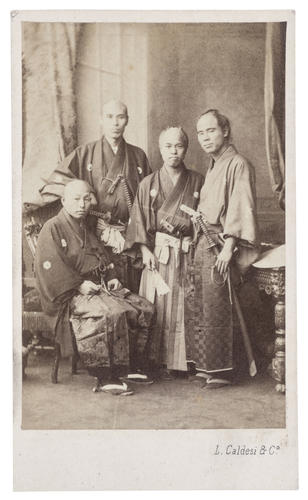

Group of Japanese Ambassadors c. 1862

Albumen print, carte-de-visite | 8.8 x 5.7 cm (whole object) | RCIN 2914637

Leonida Caldesi & Co (active c. 1860-66)

Group of Japanese Ambassadors c. 1862

-

A carte-de-visite of (from left to right): Kawasaki Dōmin (1831–81), Saitō Dainoshin (1822–71), Okazaki Tōzaemon (1837–?), Ōta Genzaburō (1835–95). All four men participated in the Takenouchi delegation sent to Europe in 1862 to renegotiate treaties between Japan and five European countries.

When the diplomatic mission reached its destination, the carte-de-visite industry was reaching its zenith; it has been suggested that up to 105 million British cartes were commissioned that year alone. Patented in 1854 by the French photographer André Adolphe Eugène Disdéri (1819–89), the carte consisted of a photographic portrait roughly 6.0 × 9.0 cm pasted on a piece of marginally larger board. The success of Disdéri’s invention is largely attributed to the fact that up to eight different portraits could be taken using a single negative plate, making the entire process cheaper, quicker and easier to control. Initially, middle- and upper-class individuals would share their cartes on the basis of acquaintance, but the format soon became central to a mass trade that made images of well-known public figures available for purchase.

Such was the demand for celebrity cartes that photographers would often photograph popular actors, artists and politicians free of charge in return for permission to distribute their image. It is not clear whether the Japanese ambassadors exploited this photographic fad to increase their visibility and influence, or whether the photographers used cartes of the ambassadors to enhance their own repertoire. Whatever the case, a number of senior members of the mission visited leading photographic houses in Paris, London, Amsterdam and Berlin to have their portraits taken. Their sittings resulted in numerous cartes that spread throughout Europe, three examples of which survive in the Royal Collection.

This carte is typical of the genre in depicting full-length figures, framed by sumptuous furniture and fabrics, against a painted backdrop.The diplomats also adopted formulaic western poses, presumably as directed by the photographer. In spite of this overt regularity, their samurai dress clashes with the ostentatiously decorated Victorian studio, capturing the tension between Japanese and western visual culture at the time.

The Takenouchi mission, and three subsequent Japanese embassies to Europe in 1864, 1865 and 1867, met with limited diplomatic success. Indeed, the final one, dispatched to the Paris Exposition Universelle, was rendered ineffective by the announcement that the government it represented had been overthrown and its power shifted to the emperor. Despite the failure of the shōgun’s ambassadors fully to achieve their objectives, the reproduction and circulation of their cartes-de-visite at a time when the cartes craze was at its peak was important in consolidating the West’s burgeoning interest in samurai manners and codes of honour. For the first time, the general public could scrutinise photographs of samurai, propelling this relatively inaccessible warrior class – soon to become obsolete – to celebrity status.

Text adapted from Japan: Courts and Culture (2020)Provenance

Possibly presented to Queen Victoria, after 1862

-

Medium and techniques

Albumen print, carte-de-visite

Measurements

8.8 x 5.7 cm (whole object)

Category

Object type(s)