Eastern Encounters

Drawn from the Royal Library's collection of South Asian books and manuscripts

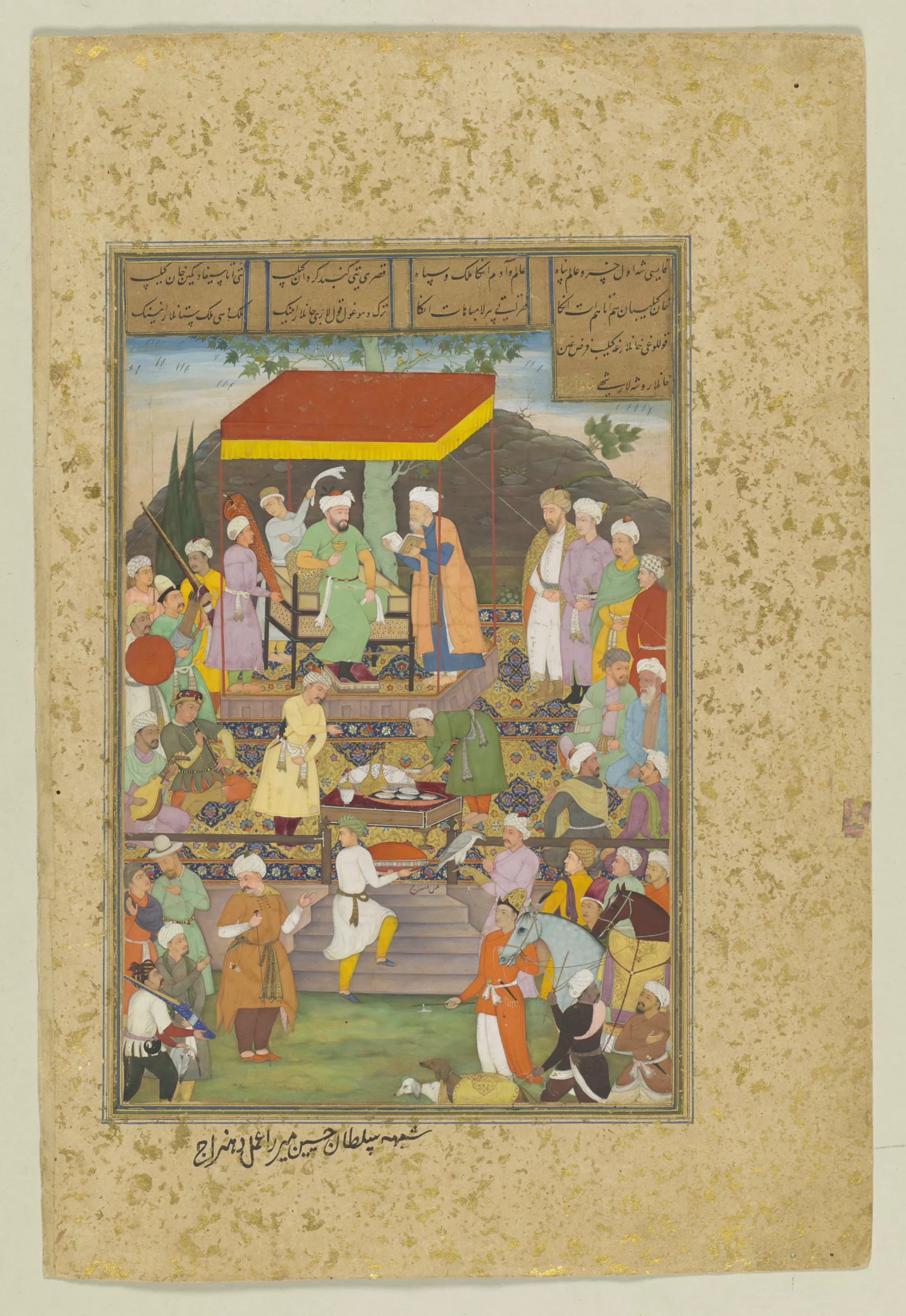

Sultan Husayn Mirza rests after a hunt by Dhanraj

Mughal, <i>c</i>.1605–10Fol. 12v from a manuscript of the Khamsa of Nava’i (see cat. no. 21) | A composite page: opaque watercolour including gold metallic paints and leaf with decorative incising on paper; text in black and gold inks on gold-flecked dark brown paper adhered onto surface; set into margins of gold-flecked paper | 34.4 × 23.0 cm (folio); 23.2 × 15.3 cm (panel) | RCIN 1005032.f

This colourful painting was commissioned by the Emperor Jahangir in apparent homage to the Timurid ruler Sultan Husayn Mirza (see cat. no. 21) and the manuscript’s calligrapher and author, all of whom can be identified in the scene. The aged calligrapher, Sultan Ali Mashhadi, stands barefoot before the throne and presents to the prince an open manuscript. To the right stands Ali Shir Nava’i, the first in a line of courtiers, wearing a gold robe of honour to mark his status as Sultan Husayn’s vizier.[83] Clamouring in the foreground are hunters with guns, bows and arrows, horses, hounds and a hawk, recently returned from their sport. Servants bring food on covered trays to a low table at the centre from which a meal is being served. On the left, a duo of musicians playing European instruments entertains the gathering. One of them also wears European-style clothing, as does another figure in a widebrimmed hat just below them.

Dhanraj is also the artist of the elephant hunt in cat. no. 12. The two works are almost polar opposites in style. Here the artist employs bold colour but with less subtlety of handling than in the earlier, delicately washed nim-qalam painting. The modelling of colour, particularly on the dapple-grey horse, and details such as the wonderful carpet fashioned with gold thread, are nevertheless highly accomplished. Many of the figures are charmingly individualised, especially the long-faced, sober-looking Nava’i, known to have been over-sensitive in temperament and quick to take offence.[84] The high horizon and prominently placed chinar tree are all elements inherited from the Iranian classical tradition, while the modular pyramid composition and use of horizontal registers and gazes as demarcations of conceptual boundaries in the presence of a ruler are features shared with contemporary paintings of the Mughal court. The notion of reflexivity – the calligrapher and the author of the manuscript physically manifested within the manuscript in the act of presenting the manuscript – is also one that was frequently explored by Jahangir’s artists.[85]

amal-e dhanraj / the work of Dhanraj

shabiha-ye sultan husayn mirza / likeness of Sultan Husayn Mirza

[83] Elements of this painting may have been taken from earlier images contemporary to the text. See also ‘Coronation of Sultan Husayn Mirza’ (Freer Sackler, Art and History Trust Collection, LTS1995.2.26, in Soudavar 1992, pp. 86–8), and painting on fol. 21r of a Gulistan manuscript written by Sultan Ali Mashhadi and owned by Hamida Banu Begum and Jahangir (Freer Sackler, Art and History Trust Collection, LTS1995.2.30, in Soudavar 1992, pp. 105–6), both of which depict Mir Ali Shir Nava’i.

[84] See Roxburgh 2015, p. 124.

[85] Portraits of artists, calligraphers and other artisans involved in the creation of manuscripts were painted in the margins of album pages and in manuscripts under the colophons. For Mughal colophon paintings, see Rice 2014.