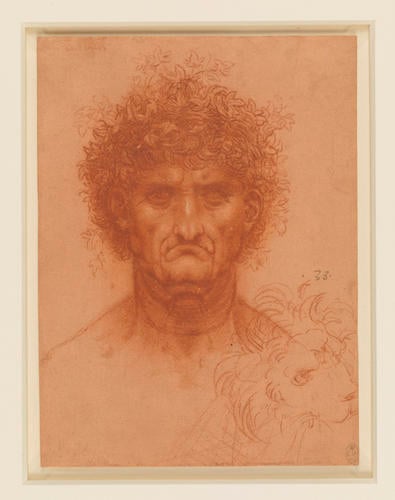

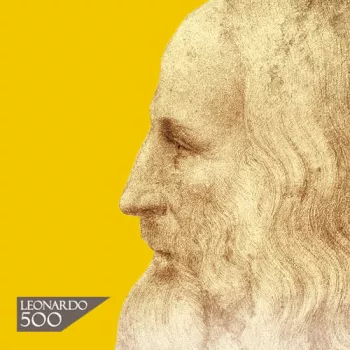

The bust of a man, and the head of a lion c. 1510

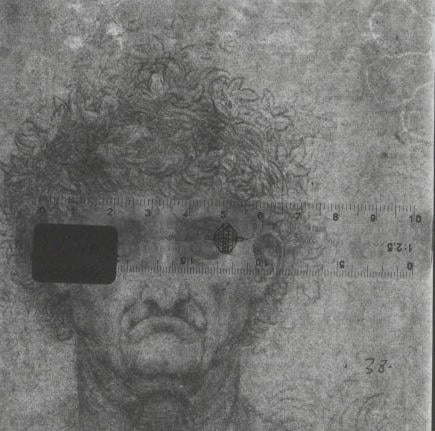

Red chalk, touches of white chalk, on orange-red prepared paper | 18.3 x 13.6 cm (sheet of paper) | RCIN 912502

-

A drawing of the head of a clean-shaven man, facing the viewer. He has a down-turned mouth and a mass of curly hair interspersed with ivy leaves. In the top left corner is some illegible writing, and below, to the right, a lion's head is lightly sketched as if to suggest a skin worn by the man. Melzi's number 38.

Early in his career Leonardo fixed on two standard male types, who recur endlessly in his drawings: an adolescent with refined features, and an older man with aquiline nose, prominent chin and beetling brow. In the last decade of his life he produced a number of independent drawings of such heads, usually in profile – exercises in form and draughtsmanship simply for his own satisfaction.

Here the lion's head appears to have been something of an afterthought, sketched as an addition to an already complete and carefully worked frontal study of Leonardo's favourite old man with beetling brow and strongly downturned mouth. It may be part of a skin worn by the man, the pelt swagged from his left shoulder across his chest and his arm through the mouth of the lion. The use of a lion's head as a shoulderpiece was a common motif in classicizing costumes of the Renaissance, especially armour, or in any context where lion pelts were worn, such as depictions of Hercules or wild men. Here the extravagant mass of hair and the wreath of ivy leaves (of which the lion's mane is a deliberate echo) would support the idea that a wild man was Leonardo's ostensible subject - he had designed costumes of wild men for a festival in 1491, though this drawing dates from over a decade after that event and cannot be related. The ivy wreath would thus seem to have no particular symbolic meaning. But the wild man was an emblem of Gian Giacomo Trivulzio, Leonardo’s patron around 1510, and it is just possible that the drawing was made in connection with some project for Trivulzio.

Leonardo may also have intended, in sketching the lion's head, to draw a parallel between its facial features and those of the man. The faces are expressionless, and Leonardo's interest lay in the permanent cast of the features. This is therefore one of the few sheets in Leonardo's oeuvre to manifest an interest in the ancient theory of physiognomics. This was based on the idea that the soul was the essential controlling force of the body, giving it shape, defining character, controlling the fleeting senses of judgement and emotion and giving them their outlet in our gestures and facial expressions. These manifestations of the soul were not infinitely variable but dependent on the balance of the humours - blood, black bile, yellow bile and phlegm. Each individual had a preponderance of one of these, which led to a certain character type, respectively sanguine (hopeful and confident), melancholic (gloomy), choleric (irascible), or phlegmatic (lethargic).

Certain animals could also be characterised according to this theory, which led to the classification of human faces according to their resemblance to these animals. The lion, for instance, was choleric by nature, and thus choleric men tended facially to resemble lions. The theory was not conceived in the context of art but as a science in its own right, and was not discussed in a treatise on art until 1504, in Pomponius Gauricus's De sculptura. Artists rarely exploited any animal-facial type other than the leonine, not least because the lion was one of the few animals whose qualities were generally positive (unlike the wolf, fox, eagle, sheep, ox, pig, ass and so on), and indeed there is no comparison in Leonardo's drawings or writings of a man's features with those of any animal other than a lion.

By 1503 Leonardo owned at least three books that dealt directly with physiognomics - an edition of the Liber Physionomiae of Michael Scot, first published in 1477; the Liber Secretorum of Albertus Magnus, published in Bologna in 1478; and Pliny's Natural History. But while Leonardo did not question the medical basis of the humours, he was the only author of the Renaissance to reject explicitly the predictive basis of physiognomical theory, and there is no evidence that Leonardo had any interest in a programmatic approach to physiognomics.

Text adapted from M. Clayton, Leonardo da Vinci: The Divine and the Grotesque, London 2002Provenance

Bequeathed to Francesco Melzi; from whose heirs purchased by Pompeo Leoni, c.1582-90; Thomas Howard, 14th Earl of Arundel, by 1630; probably acquired by Charles II; Royal Collection by 1690

-

Creator(s)

Acquirer(s)

-

Medium and techniques

Red chalk, touches of white chalk, on orange-red prepared paper

Measurements

18.3 x 13.6 cm (sheet of paper)

Markings

watermark: Flower (cut). Briquet's comparable examples are 6560, 6596, 6601.

Object type(s)

Other number(s)

RL 12502Alternative title(s)

The bust of a man